Kotlin makes Spring MVC projects a total breeze. This is a simple web application that combines a few different Kotlin techniques into a Spring Boot project. Here are few screen shots of the finished example and then we will dive into the code that makes it possible.

package com.stonesoupprogramming.kotlinspringmvc

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication

import org.springframework.stereotype.Controller

import org.springframework.ui.Model

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestMapping

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestMethod

@SpringBootApplication //This performs magic under the hood to launch a spring web application

class KotlinSpringMvcHelloWorldApplication

//Entry point to the application

fun main(args: Array) {

SpringApplication.run(KotlinSpringMvcHelloWorldApplication::class.java, *args)

}

//This is a class that we are using for our form

//Kotlin let's us one line it!

data class Registration(var firstName: String = "", var lastName: String = "")

@Controller //Tells Spring this is a controller class

@RequestMapping("/") //Tells Spring to handle web requests at the root

class Controller {

//This function will handle HTTP Get Requests

@RequestMapping(method = arrayOf(RequestMethod.GET))

fun doIndexGet(model: Model): String{

//Send a new instance of Registration back to the view

model.addAttribute("registration", Registration())

//Render the index.html page

return "index"

}

//This method handles HTTP Post

@RequestMapping(method = arrayOf(RequestMethod.POST))

fun doIndexPost(formParams: Registration, model: Model): String {

//Send a greeting message to the view

model.addAttribute("greet", "Hello ${formParams.firstName} ${formParams.lastName}")

//Render the greet.html page

return "greet"

}

//This handles GET requests for /greet.html

@RequestMapping(path = arrayOf("/greet"), method=arrayOf(RequestMethod.GET))

fun doGreetGet(): String = "greet" //Just tell it to render the greet.html page

}

Initializing the Application

Many readers are no doubt familiar with Spring Boot. Our first class in this project appears on line 11 with this code.

@SpringBootApplication //This performs magic under the hood to launch a spring web application

class KotlinSpringMvcHelloWorldApplication

Kotlin focuses on begin concise and in this is literally an empty class that is annotated with @SpringBootApplication. The annotation performs some Spring magic that does the job of initializing the Spring environment for us. Our next segment of code is the entry point to the application.

//Entry point to the application

fun main(args: Array) {

SpringApplication.run(KotlinSpringMvcHelloWorldApplication::class.java, *args)

}

Once again, there isn’t much code here, but a lot is happening under the hood that is invisible to us. We are calling the static SpringApplication.run function and passing into it the KotlinSpringMvcHelloWorldApplication class along with the supplied command line arguments. Once again, we will leave it up to Spring to prepare our environment.

Data Class

Many Java developers have no doubt made classes the are simply holders for properties along with a constructor, getters and setters, hashcode(), equals(), and toString(). Two common applications of such classes are ORM model classes and classes that can be passed back to the view. In this case we are making a class that gets passed to the view, but we are going to define it using Kotlin’s data class. The code for such a class is extremely brief.

data class Registration(var firstName: String = "", var lastName: String = "")

Using this single line of code, we make a Registration class with two properties, a default constructor, and an overloaded constructor. The class comes packed with hashcode(), equals(), toString() and when used in Java code, it will have getters and setters. We are going to pass this code back to the view in the controller class.

Controller

The Controller is another portion of Spring MVC. We use it to map HTTP requests to the appropriate methods in the class. Spring will also inject a Model class when needed so that we can pass data back to the view. Here is the controller class written in Kotlin.

@Controller //Tells Spring this is a controller class

@RequestMapping("/") //Tells Spring to handle web requests at the root

class Controller {

//This function will handle HTTP Get Requests

@RequestMapping(method = arrayOf(RequestMethod.GET))

fun doIndexGet(model: Model): String{

//Send a new instance of Registration back to the view

model.addAttribute("registration", Registration())

//Render the index.html page

return "index"

}

//This method handles HTTP Post

@RequestMapping(method = arrayOf(RequestMethod.POST))

fun doIndexPost(formParams: Registration, model: Model): String {

//Send a greeting message to the view

model.addAttribute("greet", "Hello ${formParams.firstName} ${formParams.lastName}")

//Render the greet.html page

return "greet"

}

//This handles GET requests for /greet.html

@RequestMapping(path = arrayOf("/greet"), method=arrayOf(RequestMethod.GET))

fun doGreetGet(): String = "greet" //Just tell it to render the greet.html page

}

The first line is the @Controller annotation. Our Spring boot environment has component scanning enabled, so we only need to annotate our controller class to make Spring aware of it’s existence. On line 2, we have the @RequestMapping annotation that tells Spring that the default request mapping for this class is the root of the web application (‘/’). The class contains three functions: doIndexGet, doIndexPost, and doGreetGet. Let’s talk about each in detail.

doIndexGet

This method is annotated with @RequestMapping and it handles HTTP Get requests to the ‘/’ endpoint. The function has one parameter, model : Model, and it returns a String. The model parameter is injected by Spring.

On the first line of the function, we add a “registration” attribute to the model with a new instance of Registration. Notice that in Kotlin, we do not need the new keyword and since we define default arguments for our Regsitration class, we do not need to supply an parameters. The function ends by returning the String “index” which will tell Spring and Thymeleaf (which is our template engine) which page to render.

doIndexPost

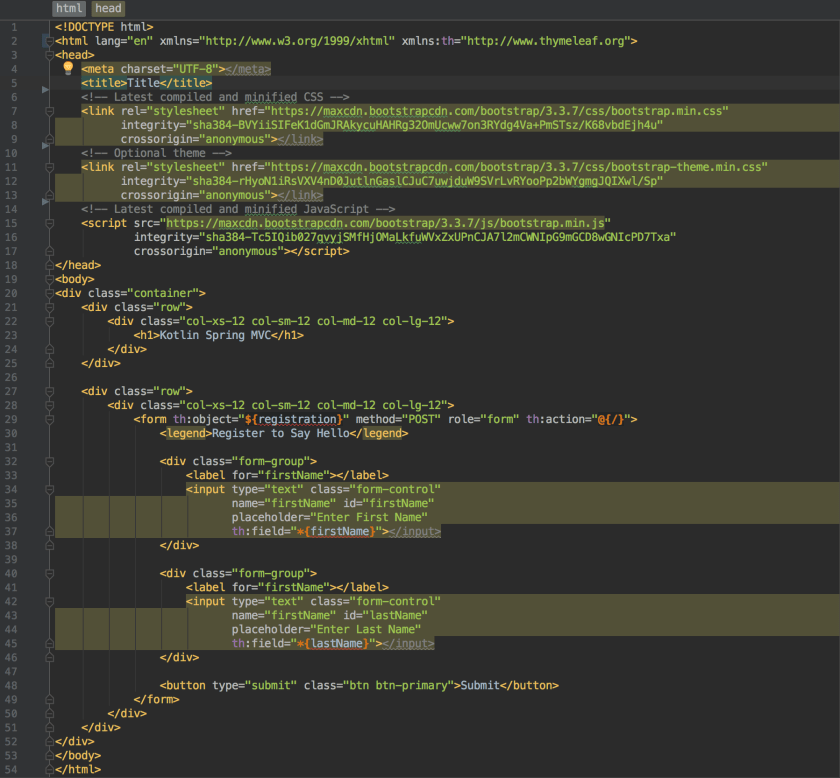

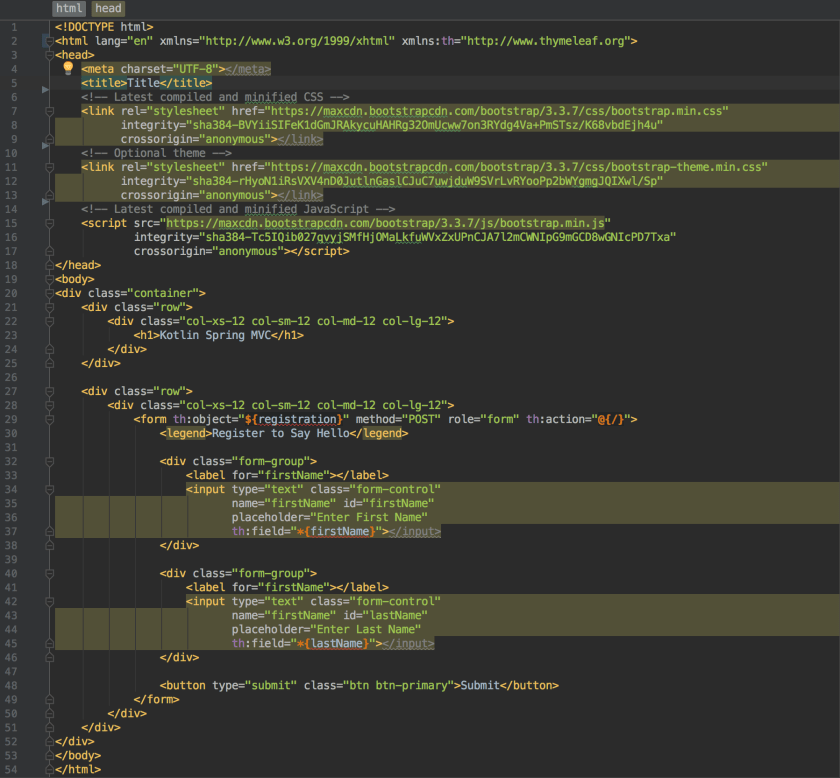

This function handles HTTP post methods as indicated by @RequestMapping(method = arrayOf(RequestMethod.POST)). It’s two arguments, formParams: Registration, and model : Model, are injected into this method by Spring. In the view, we have the following http form.

Inside of this html code you will see things like ${registration}, th:field=”*{firstName}”, and th:field=”*{lastName}”. These special tags map these input fields to the properties our Registration object that we sent back to the view in the doIndexGet function. When we click on the submit button the setter methods of the registration object are called and the values of the input boxes in the form are inserted into Registration::firstName and Registration::lastName. Then the Registration object is sent back to the server and routed to our doIndexPost method.

Once we are inside of the doIndexPost method, we can add a String to our model class.

model.addAttribute("greet", "Hello ${formParams.firstName} ${formParams.lastName}")

The second argument is the portion that I wish to discuss. Kotlin has String templating which lets us build a String using inline variables. Thus the ${formParams.firstName} will get replaced with the first name entered by the user and ${formParams.lastName} gets replaced with the last name the user entered. Then the function returns with the String “greet” which tells the web application to show the greet page.

doGreetGet

This final function is the shortest. It’s simply a function that handles the request mapping for HTTP Get when the browser navigates to the greet page. However, Kotlin let’s us define functions inline, so it’s worth talking about.

@RequestMapping(path = arrayOf("/greet"), method=arrayOf(RequestMethod.GET))

fun doGreetGet(): String = "greet" //Just tell it to render the greet.html page

All this code does is return the string “greet” so that the web application knows to render the greet.html page. Since it’s literally just returning one value, we can legally write String = “greet” in Kotlin and omit the method body.

Web Pages

For reference purposes, I have included screen shots of the web pages (they don’t seem to render properly when I use the code formatter 😦 sorry readers)!

index.html

We have already discussed how the Registration object is bound to the html form on this page. However, it’s worth pointing out that this page uses Bootstrap for page layout. Most of the code in this page was auto-generated by Intellij also, which has world class support for Bootstrap.

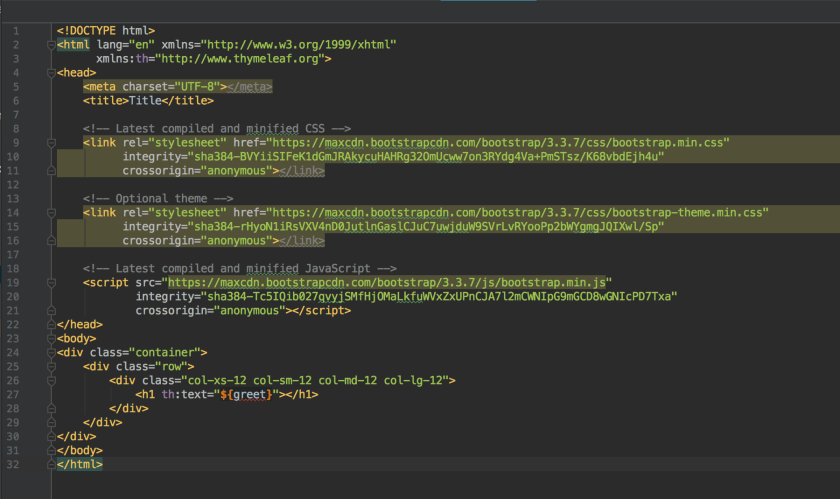

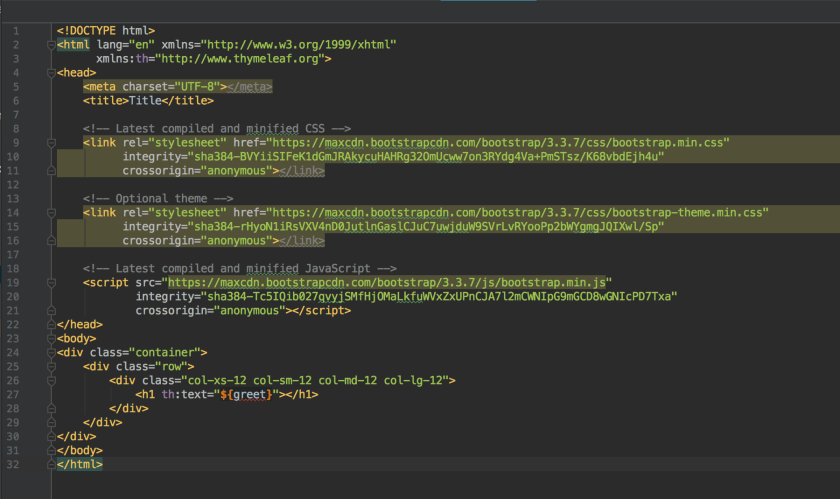

greeting.html

This is the other page that get’s returned by the controller after the user enters their name. We built a String in doPostIndex and mapped it to the key “greet” in the model. On this page, we can show that custom greeting by using th:text=”${greet}”. The template engine is smart enough to insert this greeting between the header tags.

Source

You can get the complete source code for this project from my Bitbucket page. Happy coding!